Many months ago, when I first started to write in Substack, a long-time teacher/friend/mentor told me that this was what writers did — they wrote. I had just finished my doctoral thesis and received my degree and after that, like most human achievements that seem to have a finish line, I found there was nothing. I could have had a party but it seemed too small a way to end many years of a seeking, and because I knew at once that it was not done, perhaps never will be done — the seeking, searching, writing, working, I started to take Bengali classes.

I recently read an interview of Jhumpa Lahiri in The Paris Review. After the many books she wrote in English, she turned to Italian, learning the language and making the country her home. Lahiri, much like me, said she felt like an outsider for many years in her life in America. She said she absorbed the “melancholy and solitude” of her mother who was even more of an outsider than she was. But Lahiri found her home in Italian and in Rome. Towards the end of the interview, she said, “Recently I flew back from Athens, and when the pilot’s voice came over the intercom— ‘Buonasera, benvenuti a bordo di questo volo a Roma’—tears came to my eyes, because I thought, I’m going home.”

I sent these lines to my Bengali teacher who lives in Kolkata. We spend a sizable amount of time in every class discussing the issues of homes, borders, languages and other tangents that spring like a vectors from these casual but not so casual conversations. Sometimes they lead us somewhere but just as often nowhere. Lahiri quotes Woolf in her interview, “…the only certain value is one’s own pleasure.” And our adda, the Bengali word for meandering conversations, is our pleasure.

What was curious both to me and to my Bangla teacher was that Lahiri found her home, work, muse, and belonging in a language and country not her own. Many of us make physical homes in foreign lands but to make it so beautifully and inexorably in art, work, language, written word and country is not so common, to me.

I have never lived in Bengal and in my early years in America I avoided the easy friendships that people who speak the same language can make, especially when they live in foreign lands; but after the girls were born and as the years of self-imposed exile in these so called “foreign lands” accumulated into decades, I found relief in the trips back to India, especially to Kolkata and Pondicherry. The former is the home of many of my relatives who fled across the newly made boundaries from Bangladesh to India during partition and the latter is where I grew up from when I was eleven years old.

But home is not nostalgia. Home in Bengali is desher baadi. Literally translated as my house in the country. It speaks to heritage and ancestry. For refugees though, these ancestral homesteads are left behind in a way that can never be recovered or even visited again. Like Lahiri I have been finding my home in language, though in the one my ancestors spoke for as far back as I can trace them.

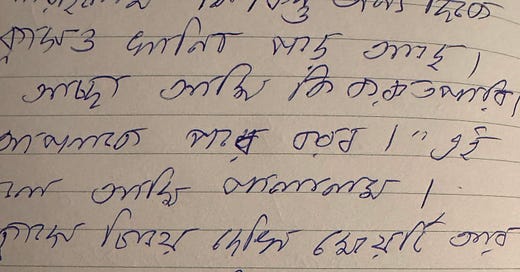

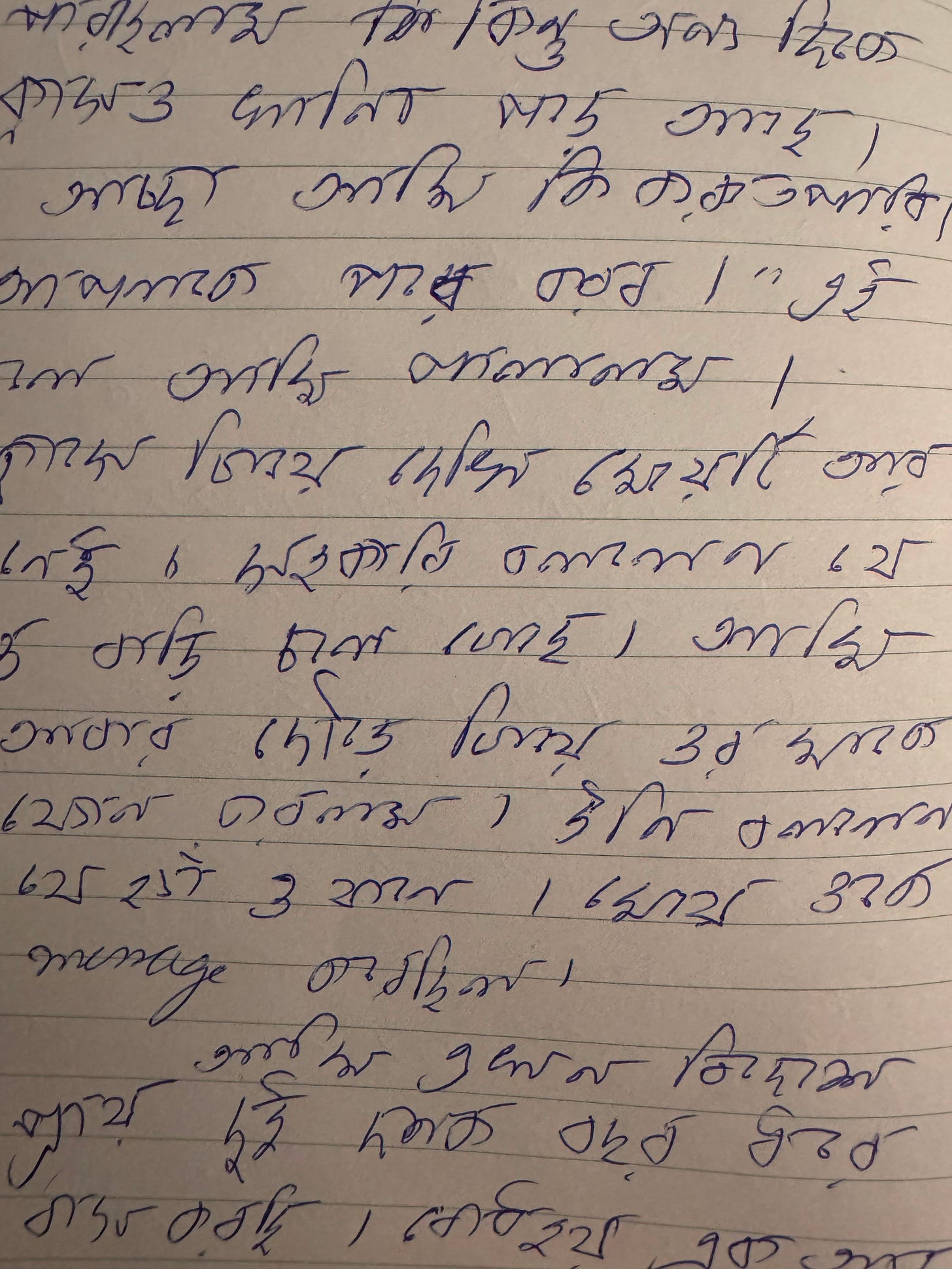

My writing in Bengali struggles to encompass the external, largely Western details of my day to day life; it is a language that often does not have equivalent words for them. So I write those English words phonetically in Bengali or just the English words themselves.

Can these meanderings on land and in language be a way to the center?

Love this!